In 2025, Manondroala Madagascar continued its collaboration with Dodo to support the development of geospatial skills within forestry and environmental institutions in The Gambia, Senegal, and Guinea-Bissau. As digital tools increasingly guide environmental monitoring and natural resource management, the program aimed to provide practical training on GIS and remote sensing methods that participants could apply directly in their daily work.

The sessions were delivered entirely online and conducted in two languages: English for participants in The Gambia, and French for participants in Guinea-Bissau and Senegal. While the overall goals were the same, the content was adapted to reflect the different backgrounds, levels of experience, and institutional needs of each group.

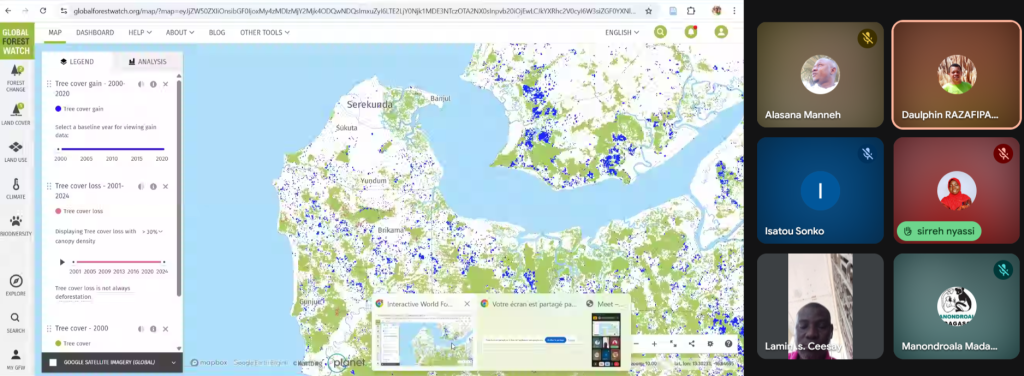

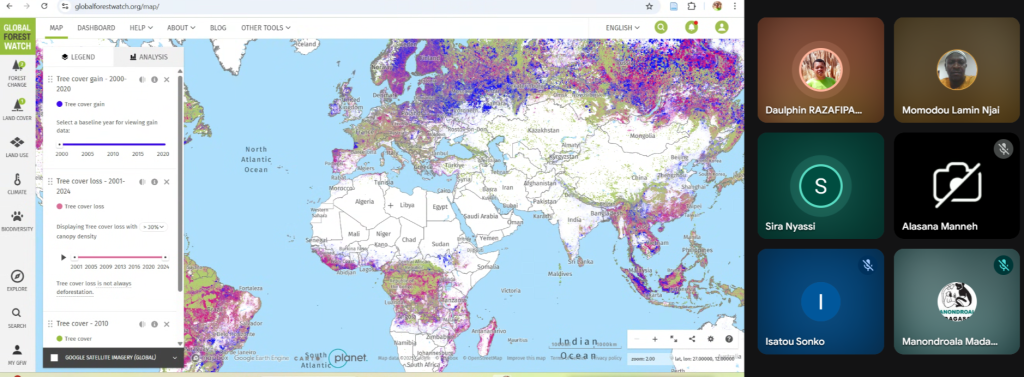

The English-language training for Gambian officials focused on building a strong foundation in QGIS and developing practical skills for forest monitoring. Participants worked through the core steps of importing and organizing spatial data, visualizing tree-cover change and forest-loss layers, interpreting satellite-based fire alerts, and producing maps suitable for reporting or field planning. Much of the training centered on strengthening the use of the software, helping participants navigate interfaces, manage raster and vector files, and follow workflows that transform raw datasets into clear geographic information. The sessions ensured that participants could begin integrating geospatial tools into their daily forest monitoring work.

The French-language training for participants in Guinea-Bissau and Senegal followed a more analytical path, reflecting the groups’ previous knowledge in basic GIS tools. Their sessions introduced methods for working with geospatial data in R, such as loading and visualizing spatial layers, calculating vegetation indices, and preparing simple classification processes that help reveal patterns in satellite imagery.

In addition, the training provided an introduction to Google Earth Engine, helping participants access image collections, applying basic scripts to visualize land cover, conducting introductory classifications, and exporting results for use in other software. While the intention was not to train programmers, the sessions demonstrated how analytical platforms like R and Earth Engine can support their work, automate tasks, and provide access to large satellite datasets that are essential for tracking landscape change.

Although the English and French sessions were focused on different topics, they were aligned in their emphasis on practical learning. Across all three countries, the training focused on improving participants’ understanding and practical use of satellite data, encouraging direct experimentation, and helping them connect the tools to their institutional responsibilities. The interactive format allowed space for questions and troubleshooting, while examples were selected to reflect real monitoring challenges faced by forestry officials.

Participants expressed that the sessions offered both clarity and practical value, helping them understand how digital tools can enhance environmental monitoring and support operational decision-making.

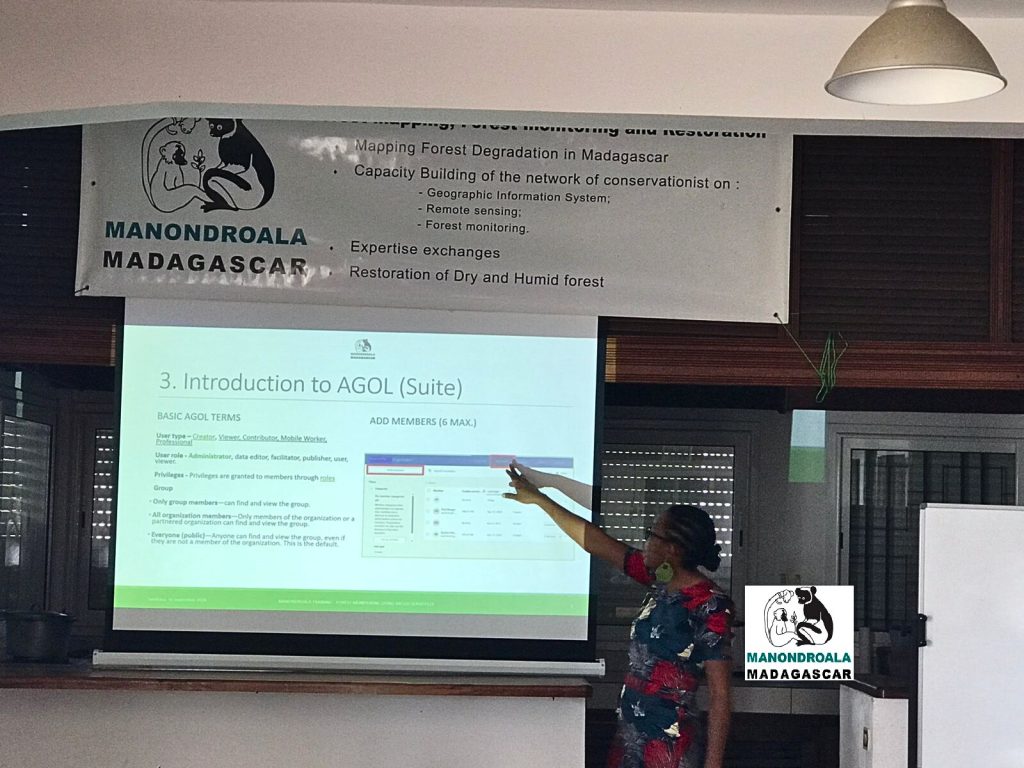

A key part of the program’s success was the work of Angela Tarimy and Daulphin Razafipahatelo from Manondroala, who prepared comprehensive materials, facilitated all sessions, and provided clear guidance. Their expertise and consistent support made the content accessible, and participants praised the structured approach that helped them navigate unfamiliar tools with confidence.

Importantly, the entire training was built on free and open-source software and openly available satellite datasets, ensuring that all methods can be replicated sustainably without reliance on commercial licenses or paid imagery.

This regional capacity-building effort builds on the Manondroala forest-monitoring tool, developed in Madagascar by FANC (Suomen Luonnonsuojeluliitto) with support from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland (UM). Designed to offer accessible methods for tracking forest cover change and supporting restoration planning, the tool is now being shared through the Tesito project with partners in West Africa, where institutions face similar environmental challenges and need scalable monitoring solutions.